Foreign Media in North Korea - How Kpop is Challenging the Regime

Movies, TV shows, and music hold power. They’re a way for us to connect through common experiences, reckon with different sides of humanity, and revel in the beauty of being here at all. They transport us to another time and place- perhaps one of our imaginations- and most importantly, allow us to dream and imagine a limitless future.

In recent years, South Korean media and entertainment has gained international recognition. People like Hyun Bin and Son Yejin, the stars of popular Korean drama Crash Landing on You, have become household names, while Parasite swept the 2020 Academy Awards and music from K-pop groups like BTS are charting globally.

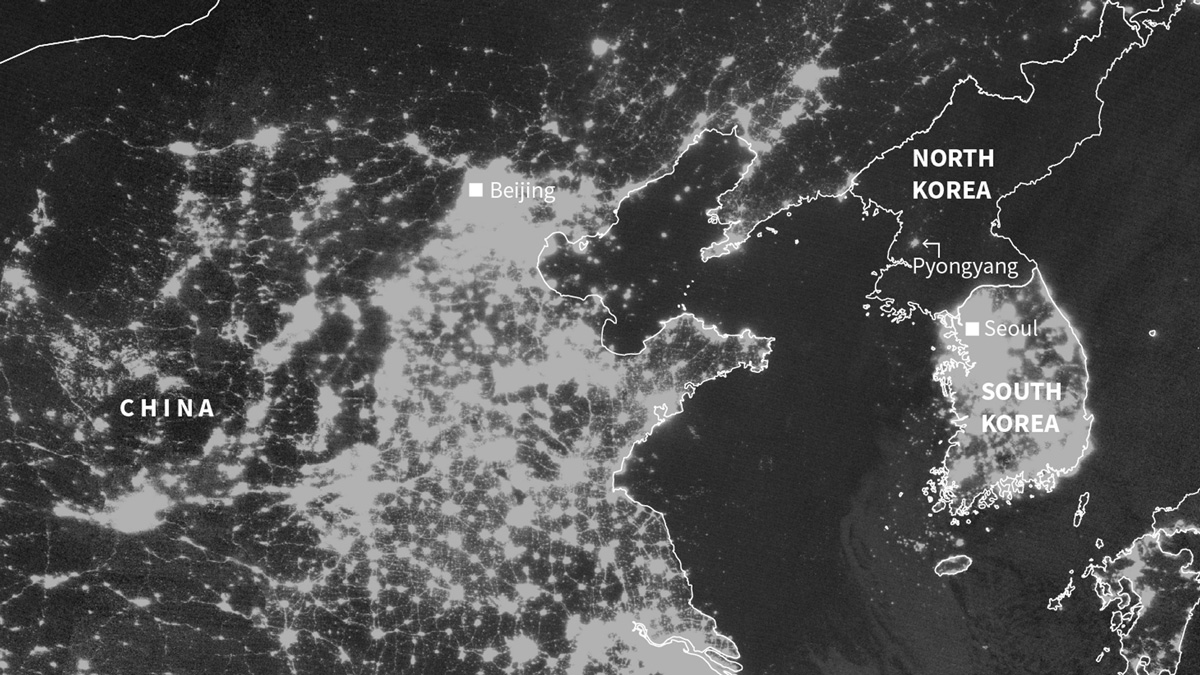

Meanwhile, just across the border, North Korea remains one of the most closed societies in the world. Yet even in the “hermit kingdom,” foreign media is accelerating empowerment of the people and change within the country!

Forced Isolation and the Regime’s Information Monopoly

The North Korean government has maintained power for decades through a system of imposed isolation, relentless indoctrination, and brutal repression. A complete monopoly on information and ideas within the country has been key- outside media threatens to challenge the legitimacy of their propaganda, and by extension, their control.

The 2014 United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in North Korea reported an almost complete denial of the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion as well as of the rights to freedom of speech, opinion, expression, and association.

The regime employs a range of strategies to enforce information control:

- Restricting movement across borders and within the country

- Random house searches

- Severe punishment, including public executions, to deter foreign media consumption and sharing

- Sophisticated digital surveillance

- Jamming phone signals and locating users through signal triangulation

- Mobile OS file signature system that only permits government-approved apps and files

The Spread of Foreign Media

Despite this isolation and unparalleled internal restrictions, the North Korean people have been quietly changing their country from within, including through foreign media access. Through market activity and the movement of people and goods across the Chinese border, they have forced the gradual opening up of their society. Movies and music are smuggled into the country on USBs, SD and MicroSD cards, and small portable media players, offering illicit access to information from the outside world.

With lights off and windows shuttered, North Koreans will watch foreign media despite the risks. If all else fails, bribes are a way for people to reduce punishment if caught. Most North Korean police and government officials rely on bribes to survive, and some defectors complain that they are actually the biggest consumers of foreign media because they confiscate so much.

Information Technology in North Korea

Within North Korea, a broad range of information technologies are available, although they should be registered with authorities. Laptops and computers officially run on a government operating system, Red Star OS, while the North Korean intranet, Kwangmyong, is air-gapped from the internet and heavily surveilled. However, in practice, many North Koreans have non-networked devices used for games, editing software, watching videos, and to copy, delete and transfer media on removable devices.

Mobile phones are also common with approximately 6 million on the North Korean network, meaning roughly 1 in 4 people have one. These North Korean phones generally cannot make international calls and the operating system limits users to approved state media (programs have been developed to bypass this security). On the other hand, smuggled Chinese phones can be used in border regions on the Chinese network. These have been crucial for staying in touch with relatives who have escaped or defected, who often send back money and information from the outside world.

Radios are the only channel of foreign media and news available real-time across the country. While they should officially be registered and fixed to North Korean stations, it is relatively easy to tamper with radio sets to pick up foreign broadcasts. In border regions, some TVs can also pick up live programming from South Korea and China. Traditionally, TVs were connected to DVD players, but newer LCD televisions also have direct USB input ports.

How Foreign Media Changes Perceptions

Among foreign media, entertainment from South Korea is particularly attractive, produced in the same base language by people with the same ancestry. They contain glimpses of rich and free realities just across the border. In comparison, domestic North Korean media seems old-fashioned and disingenuous, designed to reinforce the regime’s ideologies.

As North Koreans learn more about life, freedom and prosperity in the outside world, and their own relative poverty, the regime’s ideology and control are eroded.

“At first you see the cars, apartment buildings, and markets and you think it must be a movie set. But the more you watch, there’s no way it can be just a set. If you watch one or two [movies] it always raises these doubts, and if you keep watching you know for sure. You realize how well South Koreans and other foreigners live.”

– Danbi, escaped North Korea in 2011

Empowered by foreign media, North Koreans are exploring their creativity and potential through everyday acts of resistance- using South Korean slang, copying fashion styles, and sharing pop culture references. In this culture war, Kim Jong-un has called for crackdowns on "unsavory, individualistic, anti-socialist behavior" among young people to restrict freedom of expression.

Foreign media also facilitates shared acts of resistance. People will swap USB devices with trusted friends and neighbors, increasing confidence in one another through a symmetrical transaction. Some people may also watch and discuss movies and shows together, increasing the media’s subversive influence and creating social networks.

The Regime’s Response

During the pandemic, we’ve seen unprecedented levels of isolation and restrictions, closing off the country more than ever before. To buttress control, Kim Jong Un has simultaneously increased crackdowns and punishments on foreign media consumption. In December 2020, the “anti-reactionary thought law” made watching foreign media punishable by 15 years in a political prison camp.

While the situation is harrowing, the government’s extreme response underscores the power of foreign media. The regime recognizes that social changes driven by North Korean people are a threat to their authority and control in the long term.

Accelerating Foreign Media Access and Change

Moving forward, increasing access to outside information is one of the most effective ways to help the North Korean people and bring forward change.

Information and technology support for North Korean people has historically been an under-utilized and under-invested strategy. LiNK Labs is our area of work focused on this opportunity- we’re developing technologies, networks, and content to empower North Korean people with access to information and ideas from the outside world.

Women’s History Month: Honoring the Bravery of North Korean Women

By: Jennifer Kim

Jennifer* is Liberty in North Korea’s Field Manager. Over the years, she’s carefully stewarded our secret rescue routes and helped countless North Korean refugees reach safety and freedom.

Approximately 70% of North Korean defectors are women. Throughout their journey, they face unimaginable challenges, including human trafficking, confinement, and sexual violence.

For Women’s History Month this year, we asked Jennifer to share her experiences supporting North Korean women who have made the brave decision to escape, and bring light to the stories of real people behind the numbers and statistics.

A Transformative First Mission

When I first began this line of work, I was filled with both excitement and anxiety. “Will I be able to connect well with these people?” “Will the field be too dangerous?” Even in my position as a staff member, there were times when the situations we encountered felt riskier because I was a woman.

On my first mission, the group we brought to safety were all women. From their small requests, like asking for sanitary pads, to moments where they cautiously shared their harrowing experiences of human trafficking in China, I found that we could connect on a deeper level because I was also a woman. I realized my role wasn’t just to be a staff member, but to stand by these people as they needed me, as a fellow woman. From then on, the fear I had initially felt about this work transformed into conviction.

North Korean Women At the Forefront of Resistance and Survival

After meeting many North Korean women defectors, I’ve come to learn that there are unique challenges and experiences that only they face. Women in North Korea are not as restricted to job assignments as men, so they’re the ones actively engaged in informal economic activities. They’re running their own black-market businesses and trading smuggled goods, shifting economic power from the regime into the hands of the ordinary people.

Women also make up the majority of North Korean defectors at over 70%. In freedom, they’re leading advocacy efforts and raising awareness for this issue.

I've come to think that perhaps women in North Korean society were the first and most desperate to stand up in resistance.

At the same time, the reality is that women are more vulnerable to gender violence and crime. The moment they cross the North Korean border and set foot on Chinese soil, their precarious legal status and the fact that they are women become risk factors that can lead to human trafficking, sexual exploitation, and forced prostitution. If these dangerous situations lead to pregnancy and childbirth, women often remain in China for years, even decades, weighed down by the conflicting emotions of their longing for freedom and their maternal instincts.

All of the women I met during my first rescue mission were survivors of being trafficked into forced marriages. While there are some cases where these women meet kind families and live in a relatively less dangerous environment, most have to endure difficult lives. One woman who we rescued in 2024 said that in the early stages of her life in China, she was confined and tied up in a single room by the man who bought her. Others had to do forced labor in one of China’s many factories.

Not a News Story, But a Person’s Story

About ten years ago, I watched a video of a woman my age testifying about the hardships and sexual violence she experienced during her defection from North Korea. As a South Korean, I couldn't believe that such things were happening just across the border. Shocked and ashamed of my indifference, I cried for a long time, then resolved to do something.

North Korea used to be something I only saw and heard about through a TV screen. Now those distant news stories have become the personal experiences of the North Korean mothers and friends I’ve met in the field.

At first, I simply wanted to help as best I could. But as time went on and I met more North Koreans, my perspective gradually changed. Now, I feel like I'm not so much ‘helping’ as I am meeting incredible superwomen who have overcome tremendous adversity.

My role is to constantly remind them of their resilience and potential, so they don't forget it themselves.

“This is My First Time Being Treated Like a Queen”

After a successful mission, our team ensures our newly arrived North Korean friends have a proper meal, get some rest, and receive basic necessities. On one occasion, one woman told me, “This is the first time in my life that I have been treated like a queen.”

She had just reached freedom after ten years in a forced marriage to a Chinese man. Her words resonated with me deeply. I realized once again that our work isn't simply about helping people achieve physical freedom; it's about restoring a person's forgotten dignity.

That woman has since resettled in South Korea and runs a small shop. She’s continued to stay in contact with LiNK, sharing updates about her life. One day, she shyly announced her marriage. She’s starting a new chapter with a person she chose and wanted.

Walking Together In Solidarity

Through the friendships I’ve made and stories I’ve witnessed in the field, my connection to this issue has deepened over time. These women aren’t just “nameless” North Koreans, but people like us, living their daily lives; someone’s daughter, sister, or mother. I didn’t set out to do this work for over a decade. But day by day, hearing each story, meeting each person, and holding their hands has naturally led me down this path.

Listen to their stories, and I believe that you too will encounter a heart for the North Korean people.

– Jennifer Kim, LiNK Field Manager

*Jennifer is a pseudonym used to protect our field manager’s identity and avoid compromising this work.

Help North Koreans Win Their Freedom

From inside the country to on the global stage, North Korean women are driving change on this issue. Driven by necessity, desire to care for their loved ones, and aspirations to forge their own path in this world, their pursuit of freedom is both intentional and instinctive.

Liberty in North Korea doesn't just extend a helping hand to North Korean refugees—we’re cultivating the next generation of North Korean leaders, entrepreneurs, and advocates, and doing this work alongside them.

Become a monthly donor today at $20 per month to help more North Koreans reach safety and gain full authorship of their lives in freedom.