How A North Korean Defector Sends Money Back Home

It may seem like North and South Korea are completely cut off from each other, but even after decades of separation, channels of communication persist. Defectors who have made it to freedom are bridging the gap, connecting people inside North Korea to the world beyond. Through extensive broker networks, they send back money and information, accelerating change in the world’s most authoritarian country.

Through this process known as remittances, millions of dollars are sent into the country every year, representing huge spending power. Here’s how they do it!

Reconnecting with Family

To send money back home, North Korean refugees must first contact their families. They hire brokers to find their relatives and arrange illicit phone calls close to the border with China, where smuggled Chinese cell phones can connect to international networks. In North Korea, people are often wary of such brokers, so they may have to be convinced with codewords or childhood nicknames that only the family would know, or recognizable handwriting and photos.

To avoid being caught, contact is often made from the mountain at night, or using a series of text or voice messages sent through apps like Wechat and quickly deleted. When the call finally happens, it can be emotional for both sides.

“You hear someone say, ‘Okay you’re connected, you can speak now.’ But no one says anything to each other. You just hear a high-pitched tone, and silence. Could this be real? You’re just crying, and can’t even speak.”

– Miso, escaped North Korea in 2010

How Remittances Work

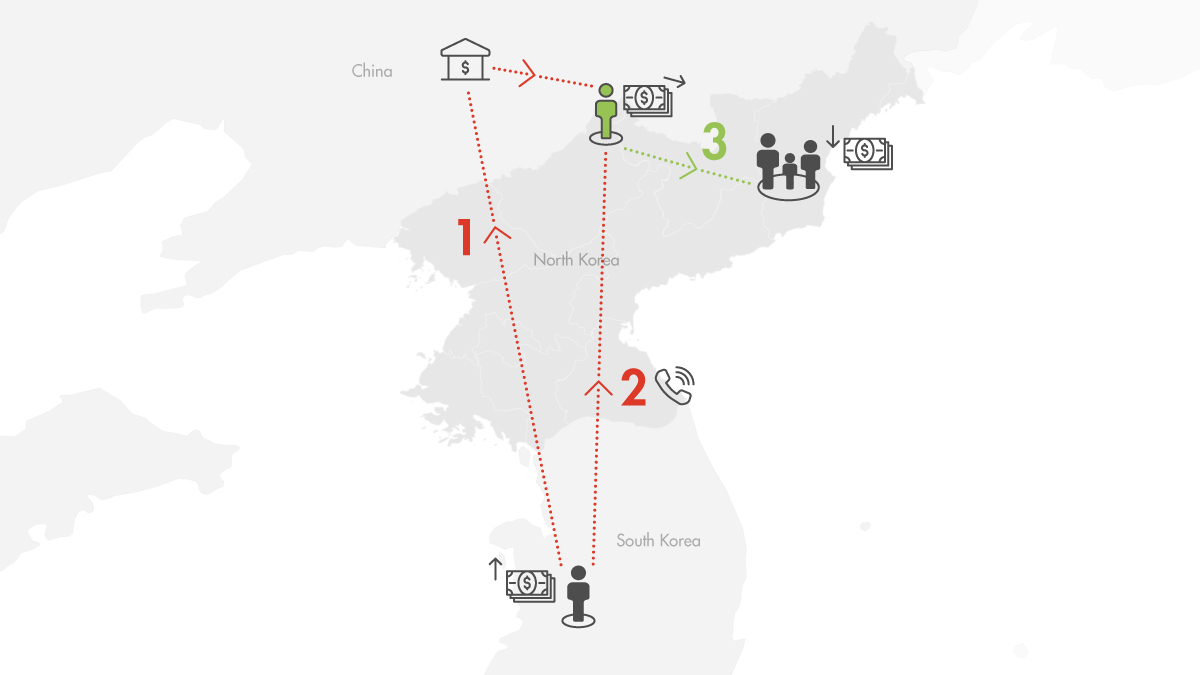

There are different ways to send money to North Korea, but a simple version involves three parties: A North Korean resettled in South Korea, a remittance broker in North Korea, and the recipient in North Korea.

- A resettled North Korean, makes a request to a remittance broker to arrange a transfer. They wire money to a Chinese account controlled by that broker.

- The remittance broker in North Korea uses a smuggled Chinese phone to confirm receipt of the funds.

- After taking a hefty commission, they give cash to the refugee’s family. The family can confirm receipt of the money by sending a photo, video, or voice message back, so the sender can be confident that they’ve not been scammed.

With this process, the remittance broker in North Korea occasionally needs to replenish their cash on hand. This could happen through the physical smuggling of cash, but oftentimes money from their Chinese bank account is used to buy goods in China that are then sold in North Korea, generating cash. In this way, physical money never actually has to cross borders.

The Power to Change Lives

North Korea is one of the poorest countries in the world, whereas South Korea is one of the richest. Therefore remittances from relatives in South Korea or elsewhere can be absolutely transformative. The money is spent on almost everything, including food, clothing, shoes, medicine, housing, transport, and bribes to keep the family safe.

“I’ve sent money back to North Korea ever since I resettled in South Korea. I send an average of $1,500 a year. My parents used the money to buy a house! They’re also going to use it to help my younger brother escape and come to South Korea.”

– Jeonghyuk, resettled North Korean refugee

With new resources also comes new opportunities. North Koreans who never had the means before can now think about starting a business at the Jangmadang, or market. Since the collapse of the regime’s socialist economy in the 1990s, the markets have become essential to making a living. The flow of remittances is increasing trade, food security, marketization, and entrepreneurship, empowering ordinary North Koreans to gain autonomy.

A Ripple Effect

Along with money, North Korean refugees send back news and information from the outside world. At first, family members back home may not want to hear about life beyond the border. Decades of propaganda villainizing the outside world can be difficult to overcome, and if caught in communication with defectors, they could face serious punishment.

But as money continues to flow in, many people can’t help but be curious- what do their relatives outside do to make a living? What kind of house do they live in? Is life there like the K-dramas smuggled into North Korea? Conversely, defectors ask their family members, what they can do with the money in North Korea? This exchange of information is incredibly valuable, providing a glimpse into the most closed society on earth.

The flow of information into North Korea erodes the regime’s propaganda and changes worldviews. As the people learn more about the wealth and opportunities of the outside world, some may also risk their lives to escape. Money sent from remittances can also be used to fund this dangerous journey.

“When I first contacted my family back in North Korea after I resettled in South Korea, they didn’t believe that I was doing well here. My parents even resented me a little for leaving. But after I sent them money and told them more about my life here, their views changed. Now they realize that the regime has been lying to them and they’re not as loyal anymore. I have become a pioneer of freedom to my family back in North Korea.”

– Jo Eun, rescued by LiNK in 2017

Agents of Change

Remittances are about more than just the movement of money. Refugees who have been separated from their families aren’t able to go back home themselves, but can still care for their loved ones in some way. Every phone call into the country and every dollar sent back represents one small step towards the day when the North Korean people finally achieve their freedom.

More than 33,000 North Korean refugees have made it to freedom, and although it has become more difficult during the pandemic, surveys report that 65.7% have sent money back to North Korea. At LiNK, we’re committed to working with and building the capacity of North Korean refugees so they can succeed in their new lives and make an even bigger impact in their communities and on this issue.

A North Korean Refugee’s Daring Escape By Boat | Gyuri Kang’s Story

Escaping from inside North Korea remains almost impossible today. Borders remain sealed by the legacy of pandemic-era restrictions, while surveillance in China continues to intensify. But in 2023, a group of North Koreans crossed into South Korean waters on a small fishing boat—a rare and extraordinary way to reach freedom. Abroad the vessel was 22-year-old Gyuri Kang with her mother and aunt.

You were never supposed to know my name, see my face, or hear my story. Because I was one of 26 million lives hidden inside North Korea.

I was born in the North Korean capital, Pyongyang. The first time the government decided my future without my consent, I was only a child. My family was exiled to a rural fishing village because of my grandmother’s religion.

In the system we were living in, not even your beliefs or thoughts are truly your own.

On my way to school, youth league officers would inspect my clothes and belongings, punishing me for even a hairpin or a skirt that was a few centimeters too short. At school, we were taught that “we live in the most dignified nation in the world,” but outside those walls, people were collapsing from hunger in the streets.

Careless words overheard by a neighbor could turn into a knock at the door in the middle of the night. The radio played government broadcasts all day long, and searching other frequencies was a risk no one dared to take. This is how the North Korean government maintains control over people. By convincing you that survival depends on submission.

I returned to Pyongyang as an adult. I majored in table tennis at the Pyongyang University of Physical Education and imagined myself making a new life, built on talent and hard work.

But reality was nothing like what I had dreamed. I came to understand a deep, painful truth: In the end, everything was determined by how well you obeyed, not how hard you worked.

Frustration and emptiness built up until I finally decided to leave Pyongyang.

I wanted to help support my mother and aunt, so I moved to the coast to try and build a life of my own. My mother used all of her hard-earned life savings to buy me a small wooden fishing boat so I could start a business harvesting clams.

That boat was more than a way to make a living. It was a daily reminder of her sacrifice, and the depth of their love and trust in me. If the money I earned with my own hands could put even one less wrinkle on her forehead, that was enough for me.

As a boatowner, I woke up early in the mornings to prepare supplies, get the crew together, and encourage them. I inspected the condition of the boat and hired people to help fix the engine and other faulty parts. Although I couldn’t go out to sea because I’m a woman, I was responsible for ensuring the ship operated smoothly.

But the harder I worked, the more government officials came to me—demanding baskets of clams and money. They justified their demands by saying: “The Party orders it,” threatening to punish anyone who refused. Every night I agonized over how to protect my people and keep my business going, and how I should respond. In those moments, I would remember the love and devotion my mother and aunt had poured into me and it gave me strength to persevere.

To escape my reality, at night I secretly watched South Korean TV shows on a television that was smuggled in from China.

My world turned upside down. With my friends who were also watching South Korean media, we would cautiously express our dissatisfaction together while also copying the hairstyles and outfits we saw in dramas. Sometimes, we would even try to mimic South Korean words or accents when talking or texting together.

But under Kim Jong Un, punishments became much more severe. Two people I knew were executed for watching and sharing foreign media. Our lives became harder, control over young people became more intense, and our resentment began to grow.

But no matter how much they tried to repress us, frustrated young people like me continued watching forbidden content as a way to forget reality. Foreign media has quietly found its way into North Korea for decades. As I grew up, it began spreading more than ever before, through USBs passed between friends or broadcasts picked up on illegal devices.

Many defectors, like me, can remember the exact episode of a TV show, a specific South Korean song, or even a traffic report, that planted the first seeds of doubt.

Of course, dramas and movies don’t tell the whole story, but they show a life that contradicts everything we were taught. And it makes you wonder: if life is so different out there, why does it have to be this way here?

I realized it doesn’t just show people that different lives exist. It gives them the belief that their life could be different. And that belief gives people the courage to choose a different future.

The thing about information is once you learn something, you cannot unlearn it. I remember watching people on my screen speak freely, laugh openly, and pursue their dreams—things that were unimaginable in North Korea. For the first time, I wondered if everything we were taught might be wrong. That doubt led to questions, and my curiosity became too strong to ignore. Now that I had seen the truth, I could never go back to the person I was before.

Escaping North Korea cannot be explained by the simple word “leaving.” This was especially true for me because I escaped together with my mom and my aunt. They had placed their trust in me when they gave me money for that boat. And now I was placing my trust in that boat to carry us across the sea to freedom.

I planned our escape in complete secrecy.

I bought a smuggled GPS device from China, carefully traced our route, observed the currents and tides, learned the patrol schedules of the guard boats, and figured out the blind spots of the coastal guard posts. I meticulously checked the condition of the boat and quietly prepared all the food and supplies we would need. I trained my body for the wind and the waves, and my mind for the terror of being caught.

Some nights I woke up in a panic. Other times my confidence crumbled and I thought, maybe I should give up and just accept the life I have. But in those moments, I imagined what waited at the end of the journey.

I wasn’t leaving just to stay alive. I was leaving so that I could live like a human being.

On the night we left, we climbed into my boat and pushed off into the dark water. I gripped the rudder and let the current carry us south, carefully navigating around the guard posts and patrol boats who were on the water looking for people like us.

I knew what would happen if we were caught. Arrest. Endless investigations. Humiliation. Public trials. Political prison camp. And the possibility that I might lose the people I loved most in the world.

My mother and aunt were trembling with fear. I had to hide my own fear to tell them what I could only hope. We will survive. We spent the night being tossed back and forth on the East Sea. Black waves lifted our boat like a toy before smashing it down again. Every crash sent water over the sides and threatened to swallow us up.

Suddenly, a patrol ship appeared. Its lights stabbed the water, blinding us, and started coming closer and closer. It was coming for us. My chest pounded so hard I felt it might burst. I thought of the sleeping pills we had brought.

We had agreed that if capture became inevitable, we would rather take our own lives. It was a fate we preferred to execution or prison camps. As the coast guard closed in, I wondered, is it time for the pills?

But I refused to give in. We were so close. I steered away from the searchlights, surrendered the boat to the churning water, and pushed on forward.

Suddenly, the patrol vessel stopped and turned back around. They could no longer chase us. We had reached the maritime border. The sea calmed, as if it was welcoming us to freedom. And as the sun rose, we saw the outline of land.

A South Korean fisherman, hearing radio reports that North Korean patrols were in pursuit, realized we were the boat being chased. He steered his boat toward us and said, "Welcome. You are safe now."

It’s been almost two years since we arrived in South Korea.

I still remember moving into our apartment and using a showerhead for the first time, experiencing hot water flowing straight from the tap. I couldn’t believe it. That day, my mother, my aunt and I took turns showering, laughing, and saying to each other, “So this is what a human life feels like.”

For the first time in my life, I could choose my studies, my job, my clothes, my hobbies—even the way I spoke—for myself. It felt like an entirely new world. We were being reborn, leaving behind a past of silence and control for a life with dignity and a future we could choose ourselves.

My mother began studying for a professional certification. And my aunt enrolled in social welfare classes to help others. I studied hard and was recently accepted into Ewha University. I have also been active in North Korean human rights activism and I even started a YouTube channel to show the world what it looks like to start a new life in South Korea.

Hope is dangerous for the North Korean government. Millions of people live with anger and sadness, but even more live in resignation. Most do not realize their rights are being violated—they don’t know what “rights” are. I once believed it was normal for the state to control every part of our lives. I thought every country lived this way.

But the moment you realize life could be different, hope begins to take root. And once hope exists, change is no longer unimaginable.

My dream is that someday North Korea will be a place where young people choose their own paths, where no one is punished for their words, and where every person lives as the true owner of their life. While so much of North Korea’s reality is dark, change is already happening. And what sparks that change is information. A single truth from the outside world, a glimpse of what life could be, can plant a seed of doubt, or ignite a spark of hope.

That’s why I speak out. If I don’t tell my story, who will tell it for me? If I stay silent, will the death of my friends, and the suffering and starvation my family endured be forgotten?

Right now, in North Korea, there is someone just like me—sitting in a dark room, secretly watching a South Korean broadcast, quietly wondering: Could I also live like that?

I want my story to prove that this hope can become a reality. I want to stand in the middle of that change. Not just as someone who escaped to enjoy freedom, but as someone determined to one day share that freedom with all North Korean people.

Freedom is not given, but it is something we can achieve. With your support, we can write a future where all North Korean people are free.

Foreign media gave Gyuri a glimpse of the outside world—and the courage to seek freedom.

Increasing North Korean people’s access to outside information is one of the most effective levers for change in the country. And that is exactly what we’re doing at Liberty in North Korea

In partnership with North Korean defectors and engineers, LiNK develops tailor-made technology, tools, and content that help people inside the country access more information more safely. These glimpses into the wider world build people’s resilience to the regime’s propaganda, and emboldens them to imagine a different future for themselves and their country.

Help fuel work that’s directly supporting North Koreans driving change on the inside.