How A North Korean Defector Sends Money Back Home

It may seem like North and South Korea are completely cut off from each other, but even after decades of separation, channels of communication persist. Defectors who have made it to freedom are bridging the gap, connecting people inside North Korea to the world beyond. Through extensive broker networks, they send back money and information, accelerating change in the world’s most authoritarian country.

Through this process known as remittances, millions of dollars are sent into the country every year, representing huge spending power. Here’s how they do it!

Reconnecting with Family

To send money back home, North Korean refugees must first contact their families. They hire brokers to find their relatives and arrange illicit phone calls close to the border with China, where smuggled Chinese cell phones can connect to international networks. In North Korea, people are often wary of such brokers, so they may have to be convinced with codewords or childhood nicknames that only the family would know, or recognizable handwriting and photos.

To avoid being caught, contact is often made from the mountain at night, or using a series of text or voice messages sent through apps like Wechat and quickly deleted. When the call finally happens, it can be emotional for both sides.

“You hear someone say, ‘Okay you’re connected, you can speak now.’ But no one says anything to each other. You just hear a high-pitched tone, and silence. Could this be real? You’re just crying, and can’t even speak.”

– Miso, escaped North Korea in 2010

How Remittances Work

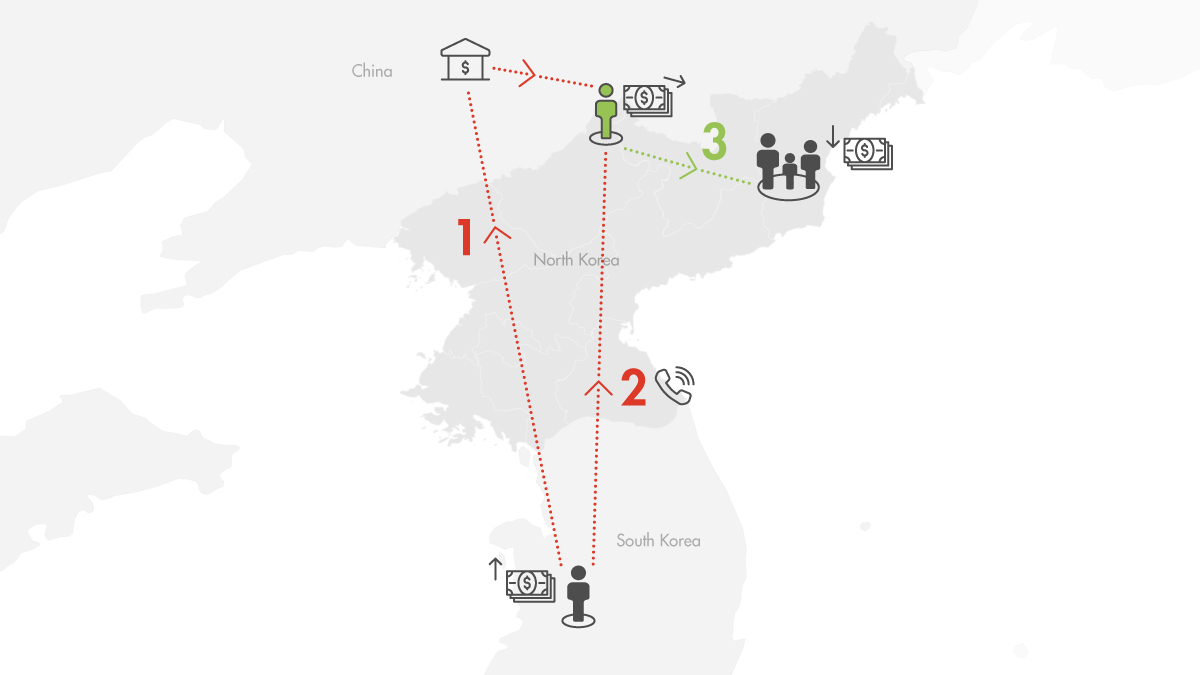

There are different ways to send money to North Korea, but a simple version involves three parties: A North Korean resettled in South Korea, a remittance broker in North Korea, and the recipient in North Korea.

- A resettled North Korean, makes a request to a remittance broker to arrange a transfer. They wire money to a Chinese account controlled by that broker.

- The remittance broker in North Korea uses a smuggled Chinese phone to confirm receipt of the funds.

- After taking a hefty commission, they give cash to the refugee’s family. The family can confirm receipt of the money by sending a photo, video, or voice message back, so the sender can be confident that they’ve not been scammed.

With this process, the remittance broker in North Korea occasionally needs to replenish their cash on hand. This could happen through the physical smuggling of cash, but oftentimes money from their Chinese bank account is used to buy goods in China that are then sold in North Korea, generating cash. In this way, physical money never actually has to cross borders.

The Power to Change Lives

North Korea is one of the poorest countries in the world, whereas South Korea is one of the richest. Therefore remittances from relatives in South Korea or elsewhere can be absolutely transformative. The money is spent on almost everything, including food, clothing, shoes, medicine, housing, transport, and bribes to keep the family safe.

“I’ve sent money back to North Korea ever since I resettled in South Korea. I send an average of $1,500 a year. My parents used the money to buy a house! They’re also going to use it to help my younger brother escape and come to South Korea.”

– Jeonghyuk, resettled North Korean refugee

With new resources also comes new opportunities. North Koreans who never had the means before can now think about starting a business at the Jangmadang, or market. Since the collapse of the regime’s socialist economy in the 1990s, the markets have become essential to making a living. The flow of remittances is increasing trade, food security, marketization, and entrepreneurship, empowering ordinary North Koreans to gain autonomy.

A Ripple Effect

Along with money, North Korean refugees send back news and information from the outside world. At first, family members back home may not want to hear about life beyond the border. Decades of propaganda villainizing the outside world can be difficult to overcome, and if caught in communication with defectors, they could face serious punishment.

But as money continues to flow in, many people can’t help but be curious- what do their relatives outside do to make a living? What kind of house do they live in? Is life there like the K-dramas smuggled into North Korea? Conversely, defectors ask their family members, what they can do with the money in North Korea? This exchange of information is incredibly valuable, providing a glimpse into the most closed society on earth.

The flow of information into North Korea erodes the regime’s propaganda and changes worldviews. As the people learn more about the wealth and opportunities of the outside world, some may also risk their lives to escape. Money sent from remittances can also be used to fund this dangerous journey.

“When I first contacted my family back in North Korea after I resettled in South Korea, they didn’t believe that I was doing well here. My parents even resented me a little for leaving. But after I sent them money and told them more about my life here, their views changed. Now they realize that the regime has been lying to them and they’re not as loyal anymore. I have become a pioneer of freedom to my family back in North Korea.”

– Jo Eun, rescued by LiNK in 2017

Agents of Change

Remittances are about more than just the movement of money. Refugees who have been separated from their families aren’t able to go back home themselves, but can still care for their loved ones in some way. Every phone call into the country and every dollar sent back represents one small step towards the day when the North Korean people finally achieve their freedom.

More than 33,000 North Korean refugees have made it to freedom, and although it has become more difficult during the pandemic, surveys report that 65.7% have sent money back to North Korea. At LiNK, we’re committed to working with and building the capacity of North Korean refugees so they can succeed in their new lives and make an even bigger impact in their communities and on this issue.

Trafficking and Exploitation of North Korean Refugees

For North Koreans hiding in China, repatriation is synonymous with death. Resolved to avoid such a fate, but with few options or protections, North Korean refugees are left vulnerable to a second wave of human rights abuses.

Among North Korean women and girls who escape to China, an estimated 60% have fallen victim to human trafficking.

Here are the stories of three women who have survived the unimaginable and are now advocating for this issue in freedom.

The Fear of Forced Repatriation

After Eunju fled from North Korea in 1999, she ended up spending years in China before finally reaching freedom.

“In China, North Korean defectors are exposed to various crimes, including sexual assault, human trafficking, forced prostitution, and labor exploitation. Those who seemed kind and willing to help were either traffickers or rapists. Promises of wages to be paid in the fall were replaced with threats—’You're from North Korea, aren't you?’

There is only one reason why the victims—North Korean defectors—remain silent: the fear of forced repatriation. This fear-driven silence perpetuates a vicious cycle of human rights violations against North Koreans in China.

On our first night in China, we were confronted with a trauma that would haunt us for a lifetime. As we walked along the road, not knowing where to go, a car slowed down and pulled up beside us. The door swung open, and someone grabbed my sister. My mother and I clung to her, desperate not to let go, but we couldn’t withstand the force of the accelerating car and were thrown aside. At the time, my sister was still just a young girl who had not even gone through puberty, yet she could not escape sexual violence. My mother couldn’t even bring herself to think about reporting the incident. She knew that if she went to the authorities, the Chinese police would capture us and send us back to North Korea before they ever caught the perpetrator.”

Soon after, Eunju’s mother was trafficked into a forced marriage together with Eunju and her sister, and they were sold for 2000 RMB (~$240 at the time).

Sold on the Way to Freedom

Hannah fondly remembers growing up with a large family in North Korea. But widespread food shortages forced her to leave her beloved hometown at 15 years old. When she finally managed to cross into China, she was trafficked and sold into a forced marriage.

“Do you remember what life was like when you were 15 years old? Maybe you were stressed about highschool, or getting your driver’s license. When I was 15 years old, I was sold to a man in China who was twice my age. For the first 6 months of captivity, I stayed away from him as much as I could. But in the end, there was nothing I could do to protect myself.”

“When I became pregnant, I couldn’t accept it because it wasn’t my choice. But then my baby arrived, and it all hit me. I wanted to give my daughter the same love I had grown up with. But I couldn’t do that without legal status or freedom. So with my one-month-old baby in my arms, I escaped once again.

Even though it was a very hard and dangerous journey, we ran together towards freedom, towards a future that guarantees our safety and hope.”

A Mother’s Impossible Choice

Joy fled from North Korea when she was 18 years old. When she reached China, the broker who arranged her escape went back on their word and immediately demanded to be repaid.

“She told me my only option was to be sold into marriage to a Chinese man so the brokers could take my bridal cost as payment. I couldn't even think of refusing because I was afraid they would do something bad to me or drop me off somewhere alone to get caught by the Chinese police and sent back to North Korea. At that point, I realized that I was trapped.”

Joy was sold to an older Chinese man for $3,000. She searched for any way to escape, but soon became pregnant and gave birth to her daughter. For two years, she raised her child and began to lose hope of ever reaching freedom.

Then in 2013, Joy was connected to LiNK’s network. She felt it was her last chance to take back control of her life. But she faced an impossible decision. Her daughter was still very young, and it would be incredibly risky to escape together. Ultimately, Joy decided to leave her behind.

“I cried every day thinking of my daughter. Before we started moving to get out of China I stayed with some other defectors…I didn't want to cry in front of [them], so I cried behind a curtain. I found another North Korean woman crying there because she also left her child. We ended up hugging each other and crying together.”

Stories of Hope

Eunju, Hannah, and Joy’s stories echo that of thousands of North Korean women who were sold on the way to freedom. But they’ve refused to let their painful experiences prevent them from living full lives, instead turning them into sources of strength, fueling their work on this issue.

Eunju is now living in South Korea with her mom and sister. She co-authored a book about her journey, A Thousand Miles to Freedom, with journalist Sebastein Falletti to make sure stories like hers are not forgotten.

Hannah is also in South Korea raising her daughter, who will never know a life without freedom. In 2022, Hannah joined LiNK’s Advocacy Fellows program to develop her capacity as a leader and advocate for this issue. She traveled across the US alongside other young activists, sharing her story at universities, churches, Fortune 500 companies, and with key stakeholders on Capitol Hill.

Joy was also a LiNK Advocacy Fellow in 2019. Today, her advocacy continues in the classroom, as an educator at an alternative school for the children of North Korean mothers. Some of her students were born in China while the mothers were in forced marriages—a circumstance that is deeply personal. Joy is beloved by the children, and strives to help them navigate their complex identities and relationships with their parents.

All the while, Joy has kept in touch with her daughter through video calls and messages. Last year, she was finally able to bring her daughter to South Korea!

What You Can Do to Help

The trafficking of thousands of North Korean women and girls is one of the most rampant and egregious human rights violations happening today. Yet it often does not get enough dedicated attention amidst all the dangers and abuses that North Koreans face—an alarming reminder of the gravity of this issue.

LiNK rescues North Korean refugees without cost or condition, and provides crucial resettlement support during this period of transition. We’re one of the only organizations still doing this work since the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, we've helped almost 1,400 North Korean refugees and their children reach freedom.

It is more urgent and important than ever that we carry on this work. Right now, our field team is actively in communication with North Korean refugees hiding in China, many of them women who were trafficked or sold into forced marriages, and coordinating their escape. Help bring them to safety and freedom.